Latest News

Shah Bano Case

Nowhere have the contradictions posed by an Islamist solution become more evident than in the case of a South Asian Muslim divorcee who sought support from her husband through the court system. To examine the case of Shah Bano is to call attention to the pivotal yet problematic role of one mode of governance, the judiciary, as it functions in the three major Muslim states of South Asia: India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. I will argue two points that emerge when one looks at women as an independent category and the judiciary as a crucial dimension of governance. The first is that women are made to represent the cultural norms shared by men and women alike throughout Muslim South Asia. The second is that court cases involving women’s legal rights not only reflect boundary markings between Muslims and other communities, they also heighten tensions about their maintenance, even as they complicate notions of what it is to be both Asian and Muslim in the late twentieth century of the common era.

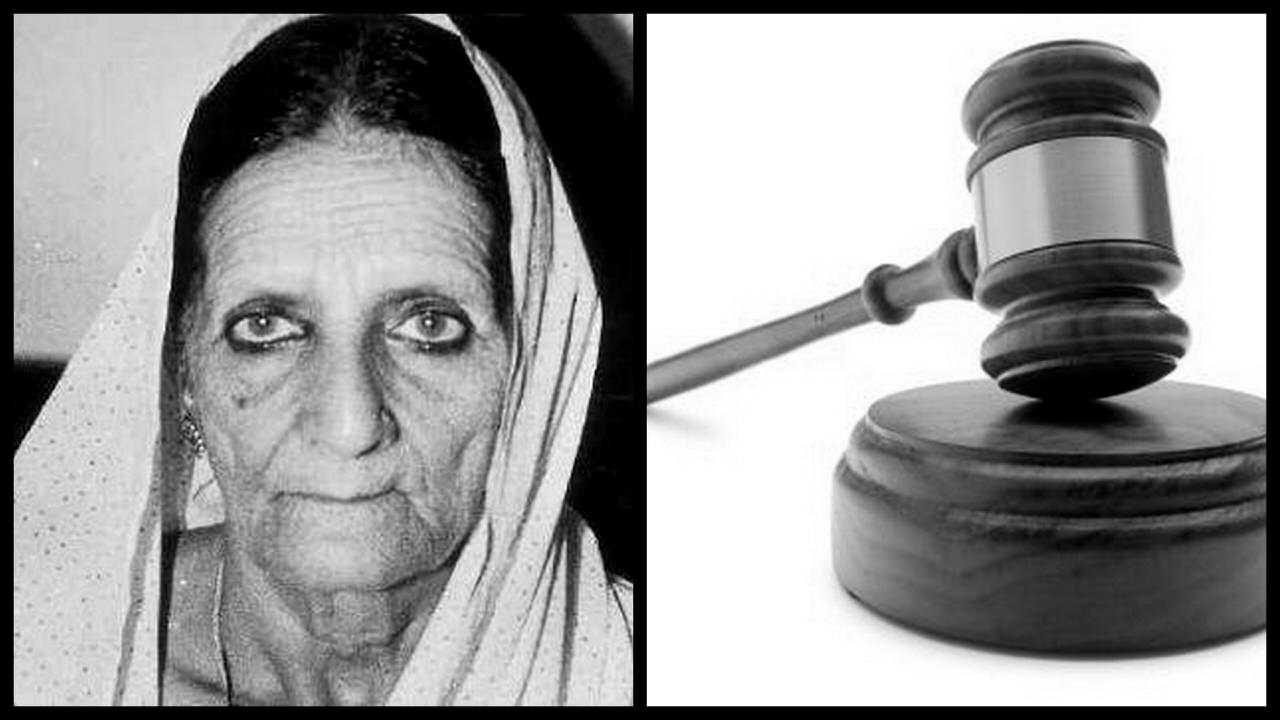

Shah Bano was the daughter of a police constable. At an early age, she had been married to her first cousin, Muhammad Ahmad Khan. During more than forty years of marriage, she had borne him five children. Then one day in 1975, according to her account, he evicted her from their home. At first, he paid her a maintenance sum, as was required by Islamic law, but he ceased payment after some two and a half years. When she applied to the district court for redress, he divorced her. Uttering the formula disapproved by the Prophet but authorized by the Hanafi School of law, he declared: ‘‘I divorce you, I divorce you, and I divorce you.” At that point they were fully divorced, but, complying with a further provision of Islamic law, Muhammad Ahmad Khan repaid Shah Bano the dower of about three hundred dollars that he had set aside at the time of their marriage.

Legally he had fulfilled all his responsibilities to her. Shah Bano, however, was left impoverished. She had no means to support herself, having worked only as a housewife for over forty years in the domicile from which she was now debarred. She sued her former husband by going to the magistrate of a provincial court. The magistrate ruled that Muhammad Ahmad Khan, having violated the intent of Muslim Personal Law, was obliged to continue paying Shah Bano her maintenance. It was at that point that Muhammad Ahmad Khan appealed the High Court’s decision. A lawyer himself, he took the case to the Indian Supreme Court, arguing that he had fulfilled all the provisions of Muslim Personal Law and hence had no more financial obligations towards his former spouse.

The Shah Bano case dragged on for another five years. Finally, in 1985, seven years after she had begun litigation in the lower courts, Shah Bano has vindicated: The Indian Supreme Court upheld the Madhya Pradesh High Court judgment, and her former husband had to comply with its verdict. The Supreme Court justices, in dismissing Muhammad Ahmad Khan’s appeal, cited the Criminal Procedure Code of 1973, one section of which referred to ‘‘the maintenance of wives, children, and parents.’’

It is no small irony that Shah Bano’s legal vindication came just as the International Women’s Decade was ending, but the favorable outcome of her case had more to do with a legislative act than with public advocacy of women’s rights: it was a change in the Code of Criminal Procedure, enacted in 1973, that made possible the reconsideration of provisions for divorced Muslim women. Throughout the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, there was no uniform manner of applying Muslim family law within the lower courts. On the one hand, the number of rules applied to questions of marriage and inheritance was restricted, while on the other hand, they were enforced through a strict hierarchical structure where appeals moved haltingly from a subordinate district judge to a state high court to the London Privy Council, replaced after 1947 by the Indian Supreme Court.

Ten years after Independence, Parliament passed an All India Criminal Procedure Code that applied, as its title suggests, to all Indian citizens, whatever their religious aviation; one of its provisions stipulated ‘‘the maintenance of wife, children, and parents.’’ It was that provision which the Supreme Court justices cited in the 1979 and 1980 cases again in 1985 when they ruled in favour of Shah Bano and against Muhammad Ahmad Khan. The case of Shah Bano became decisive for one reason: its timing. It did not occur in the mid-1970s when Mrs. Gandhi’s declaration of a state of emergency had muzzled the court system, nor will it occur again in the mid-1990s, for reasons what will be made clear below.

It was the changed climate of religious identity in the mid-1980s that set the stage for the Shah Bano debacle. There were several necessary conditions, but the one sufficient condition was Muslim Personal Law, that is, a law that applied to the personal status of each Muslim within the family domain. Personal law becomes the litmus test of Indian Muslim collective identity, its fragility underscored by the creation in 1972 of an All India Muslim Personal Law Board to maintain and defend its application. The case came to public attention in the aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination at the hands of Sikh extremists. Riots in Delhi and elsewhere had shredded the myth of communal harmony in the Republic of India. Everyone had become more aware and more worried about his or her markings as a Hindu or a Muslim or a Sikh or a tribal. When Sikhs, not Muslims, had been the primary targets of the Delhi riots, Muslims still felt vulnerable. Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress-I was then the ruling party. When Congress-I supported the Supreme Court decision, an incensed Muslim politician ran against the Congress-I candidate (who also happened to be a Muslim).

The role of the press in dramatizing the Shah Bano case has been considerable. In the volume of print and decibels of emotion, it exceeds all other tragedy-laced spectacles, even the storming of the Sikh Golden Temple in Amritsar, even the assassination of Mrs. Gandhi and later her son, Rajiv. It exceeds even the Rushdie affair, with which it has sometimes been linked, notably by Gayatri Spivak. The Shah Bano case exceeds all these because it concerns a process that has tapped into communal fears, and drawn out appeals to communal loyalty, not witnessed since independence. Its only competitor for sustained media attention is the Ayodhya mandir/Babri masjid dispute.

Ayodhya becomes the sequel to Shah Bano since it was the latter that pushed Muslim-Hindu antagonism to new levels. Unlike the local protagonists of previous communal riots, the India-wide Hindu protagonists of Ayodhya’s sacral purity were used in the media to stage a grievance identical to that of the Shah Bano case, namely, that Muslim and Hindu worldviews were finally in-commensurate and that the Republic of India could not grant both equal representations.

The mid-1980s were such a time of crisis for many Indians. India’s Muslim ‘‘fundamentalists’’ challenged the Shah Bano ruling at a moment when the Centre seemed to be unraveling. Their appeal to Parliament to reverse the Shah Bano decree seemed implausible, and the uproar about Shah Bano would have quickly subsided had their appeal failed. But for a variety of political considerations both the Congress-I and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi perceived themselves as vulnerable to ‘‘the Muslim vote.’’ Out of expediency the Indian Parliament in 1986 passed a bill often referred to as the Muslim Women’s Bill.

That bill withdrew the right of Muslim women to appeal for maintenance under the Criminal Procedure Code. In other words, after 1986 Shah Bano could have no successors, for the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Bill, in fact, discriminated against Muslim women: it removed the right of any Muslim woman to juridical appeal for a redress of the award made to her under Muslim Personal Law. But, Shah Bano subsequently rejected the court verdict in her favor and occasioned still another round of debate about the meaning of her subjectivity as a Muslim woman.