Latest News

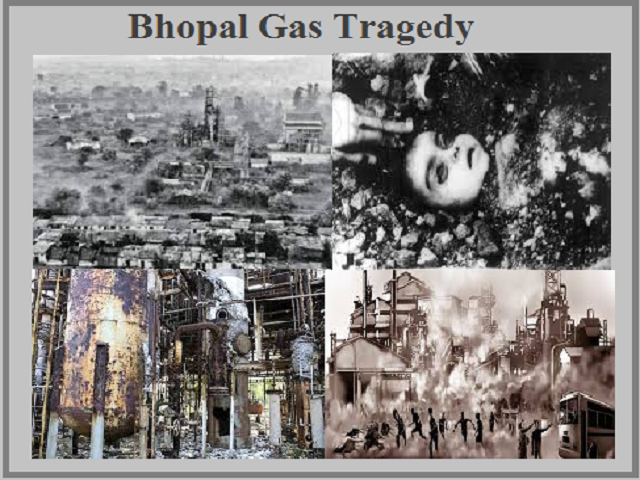

Bhopal Gas Tragedy: An Overview

M.C Mehta's case is the famous tort law case, which brought in the change in the principle of Absolute Liability in India. Shriram Food and Fertilizer Industry, a subsidiary of Delhi Cloth Mills Limited, was engaged in the manufacturing of dangerous chemicals like caustic soda, choline, hydrochloric acid, stable bleaching powder, superphosphate, Vanaspati, soap, sulphuric acid, alum anhydrous sodium sulfate, and active earth. Looking from the ground zero, these various units are all set up in a single complex situated in approximately 76 acres and they are surrounded by thickly populated colonies such as Punjabi Bagh, West Patel Nagar, Karampura, Ashok Vihar, Srinagar, Shastri Nagar and within a radius of 3 kilometers from this complex there is a population of approximately 200,000. The caustic chlorine plant was commissioned in the year 1949 and it has the strength of about 263 employees' including executives, supervisors, staff, and workers.

When one begins to look at the whole gamut of cases in environmental jurisprudence in India that M C Mehta has contributed to as a proactive pro bono public, one is sure to be baffled. His contribution has been unmatched and the cases in which he has filed the petitions himself have gone on to become landmark judicial pronouncements on both environmental law and constitutional law in India. His interventions have brought about relief to millions of Indians who otherwise would have suffered due to unmitigated ill-effects of environmental degradation and pollution.

MC Mehta’s cases have established the following seminal principles in Indian environmental jurisprudence:

- The constitutional right to life extends to the right to a clean and healthy environment.

- Courts are empowered to grant financial compensation as a remedy for the infringement of the right to life.

- Polluters should be held absolutely liable to compensate for the harm caused by their hazardous activities.

- Public resources that are sensitive and of high ecological importance must be maintained and preserved for the public.

- Similarly, the government has a duty to prevent environmental degradation. Even if there are prevailing scientific uncertainities, the implementation of preventative measures regarding it should not be delayed wherever there are the possibilities of serious or irreversible harm or damage.

- Green benches should be established in Indian High Courts which will be dealing specifically with the environmental cases.

In January 1998, the SC acknowledged and welcomed the constitution of the Environment Pollution (Prevention and Control) Authority (ECCPA or the Bhure Lal Committee) to look at the various environmental pollution matters that were faced by the National Capital Region. Even after this committee was constituted, there was no progress in resolving the problems of pollution that persisted in the region. This invited strict admonition by the SC on more than a few occasions.

On the basis of Bhure Lal committee recommendations, the SC on 28 July 2008 issued several directions, of which two are relevant to this case. First, that the ‘city bus fleet was to be steadily converted to a single fuel mode of CNG by 31-03-2001’. Second that ‘no eight-year-old buses were to ply except on CNG or other clean fuel after 1st April 2000’. When the deadline of 31 March 2001 was found to be too onerous and close, many applications were filed by the bus operators in the NCR demanding an extension of the deadline to convert the entire fleet of commercial buses to CNG.

The applications for extension contained the following reasons on behalf of the applicants: difficulties being faced by the transporters because of the non-availability of CNG conversion kits free from all defects; conversion of CNG at reasonable prices; lack of stabilization of CNG technology in respect of public transport; and the non-availability of CNG and CNG cylinders.

Justice Bhagwati interpreted and applied the secondary view of Strict Liability which was established in the famous case of Ryland v. Fletcher, establishing that if a person who brings on to his land and collects and keeps there anything likely to do harm and such thing escapes and does damage to another, he is liable to compensate for the damage caused. This rule applies only to the non-natural user of the land and it does not apply to things naturally on the land or where the escape is due to an act of God and an act of a stranger or the default of the person injured or where the thing which escapes is present by the consent of the person injured or in certain cases where there is a statutory authority. Considering the century in which the rule was evolved and the present scenario, when all the developments of science and technology had not taken place, could not have afforded any guidance in evolving any standard of liability consistent with the constitutional norms and the needs of the contemporary economy and social structure, and modern industrial society with highly developed scientific knowledge and technology where hazardous or inherently dangerous industries are necessary to carry on as part of the developmental program, the court did not feel inhibited by the existence of the exception in strict liability.

Rather the Supreme Court of India felt that the law has to grow with the society in order to cater to the needs of the fast-changing society and keep abreast of the ever-increasing economic developments taking place in the country.

However, the judgment differed from Ryland V. Fletchers in the following ways:

- The rule laid down in C Mehta v. UOI is free from all conditions laid down in Ryland v. Fletcher. The only necessary requirement is that the defendant should be engaged in a hazardous or inherently dangerous activity and that harm results to anyone on account of an accident in the operation of hazardous or inherently dangerous activity.

- The rule in Ryland v. Fletcher will not cover cases of harm to persons within the premises for the rule that requires escape of the thing, which causes the harm from the premises. The new rule makes no distinction between the persons within the premises where the enterprise is carried on and persons outside the premises for the escape of the thing causing harm from the premises is not a necessary condition for the applicability of the rule.

- Damages awardable where the rule in Ryland v. Fletcher applies will be ordinary or compensatory whereas in Mehta’s case the court can allow exemplary damages and the larger and more prosperous the enterprise, the greater must be the amount of compensation payable by it.

We can see a part of mischief statutory interpretation applied in the judgment as the principle of strict liability was introduced to make the people who have dangerous material in possession liable for any injury caused to the public due to the hazardous material in their possession, it had some limitation according to the era it was developed in and now, 2 centuries later the society demand changes in the principle according to the development in technology and society, keeping the intention of the lawmaker in mind. Had the courts not have interpreted the rule of strict liability in a different way the courts would have let the case like Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster go escort free, with no damages being paid to the victims who got no benefit from the companies but it very much endangered their lives and stagnating the aim of India to become a “welfare state” by handling both the development of scientific technology that inherently includes hazardous substance and to protect the people of India against injustice.