Latest News

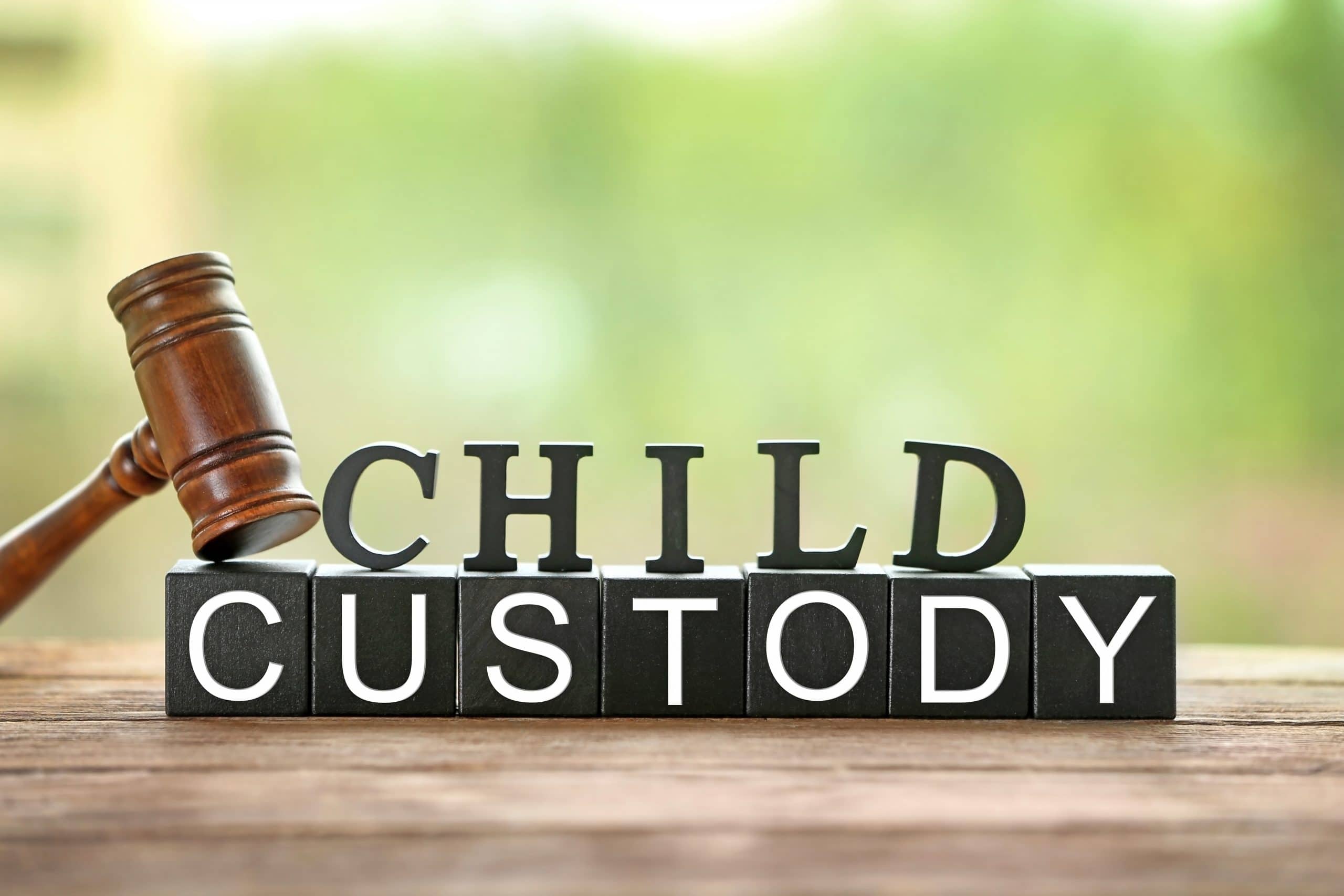

SC: PREFERENCE OF THE MINOR CHILD IS GIVEN IMPORTANCE IN MATTERS OF PARENTAL CUSTODY.

In a decision concerning transnational child custody, the Apex Court is based on section 17(3) of the Guardian and Wards Act, 1890, which specifies that the Court may recognize the preferences of a minor if he/she is old enough just to develop an intelligent preference.

"According to Section 17(3), the child's interests and preferences are of crucial significance in deciding the matter of custody of the minor child. Besides, Article 17(5) specifies that no individual shall be named or proclaimed by the Court to be a guardian against the child will," the Court noted.

This section 17(3) of Guardian and Wards Act,1890 was adopted by the 3-Judge Bench, consisting of UU Lalit, Indu Malhotra, and Hemant Gupta (2:1), thus providing custody of a child to his father, who is based in Kenya after having had a personal interaction with the kid in Chambers during the course of the proceedings, to ascertain his desires and wishes.

In the present case, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the theory (Smriti Madan Kansagra v. Perry Kansagra) that, in the exercise of parental authority, the primary and paramount concern must be to safeguard the rights and security of the child.

Therefore, to determine what was in the best interests of the kid, the Court had to take note of different considerations. These leading considerations were set out in the case of Nil Ratan Kundu v. Abhijit Kundu (2008) and were also set out in Section 17 of the GWA.

In fact, Article 17(3) states that 'If a minor is old enough to form an intelligent choice, the Court can recognize that preference.'

The Court held that, in the present case, the question of custody of the minor relied on the "overall analysis of the holistic development of the child, which had to be decided based on his interests as required by Article 17(3) ..."

Such consideration, as the Supreme Court noted, could be seen from the intimate contact of the Courts with the minor, and the preference of the minor could be of vital significance in allowing the Court to make a judicious decision on the matter of his or her custody.

The Court then continued to analyze the connection between the Court and the minor child and set forth its conclusions.

"We found that Aditya was self-confident and articulate because of his age, who was relaxed and at ease in engaging with us. He had a great deal of insight regarding his interest in seeking education abroad and was interested in going to the United Kingdom and other locations. He has expressed profound love and admiration for his mother and Nani. Around the same time, we found that he had a deep connexion and attachment to his father and his paternal grandparents."

Noting that, according to Section 17(3), the wishes of the child were of paramount significance in deciding the matter of custody of the child, the Supreme Court concluded that it would be in the best interests of the child to pass custody to the child's father as though the preferences had not been granted due consideration and that it may have an adverse psychological effect on the child.

"Because of the numerous personal experiences which the courts have had at different stages of the trial, from the age of 6 years to the present age of almost 11 years, we have concluded that it would be in his better interests to pass custody to his parent. If his preferences are not given due regard, it could have an adverse psychological impact on the child," the Court observed."

The Bench also extended the idea of "mirror order" when allowing custody of the child's father based in Kenya. Justice Hemant Gupta disagreed with the majority decision that the custody of the boy should remain with his mother in Delhi.

In a case involving transnational custody of a child, the Supreme Court applied the concept of 'mirror order.' Where a court allows a child to be transferred to a foreign country, it may impose a condition that the parent in a foreign jurisdiction also obtains a similar custody order for the child from the competent Court in that country. Such an order is called a 'mirror order. This situation is imposed to make sure that the courts of the foreign jurisdiction also put on notice regarding the issue and to ensure the protection of the child.

The mirror order is passed to ensure that the courts of the country in which the infant is relocated are aware of the provisions that have been made in the country in which he normally lives. Such an order will also protect the needs of the parent who is losing custody, ensuring that the rights of visitation and conditional custody are not compromised. The judgment recognized that the term had its roots in the English courts. Such directives shall be passed to protect the rights of a kid who is in transit from one jurisdiction to another. Mirror directives have been described by the courts as the most successful method to achieve security measures.

The Apex court explained that a 'mirror order' is ancillary or auxiliary in character and supportive of the order passed by the Court, which has practised primary jurisdiction over the custody of the child. The judgment of the Court, which had exercised primary jurisdiction of the custody of the minor child, is although not a matter of binding obligation to be pursued by the Court where the child is being transferred, which has passed the mirror order. The judgment of the court exercising primary jurisdiction would, however, have great persuasive value, explained the judgment.

Document: