Latest Articles

Montesquieu’s Theory of Separation of Powers: How it has been adopted in India

“Power corrupts and absolute Power tends to corrupt absolutely” ( said Lord Acton). For any democratic government to remain stable and function efficiently as well as effectively, the holders of power need to be put on a check against each other. This was the underlying principle behind what was propounded by Baron de Montesquieu in his book Esperit de Lois 1748. The Doctrine of Separation of Powers deals directly with the three organs of the government - the legislature, the judiciary and the executive - and tries to instil exclusivity in their operation. The fact of the matter remains that the Doctrine of Separation of Powers, as put forth and envisioned by Montesquieu has not been implemented in its strict sense in India because it describes an idealistic situation. In the Indian context, the three organs of government cannot be separated into water-tight compartments and an adaptive and flexible principle of separation of powers is followed instead.

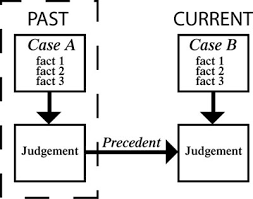

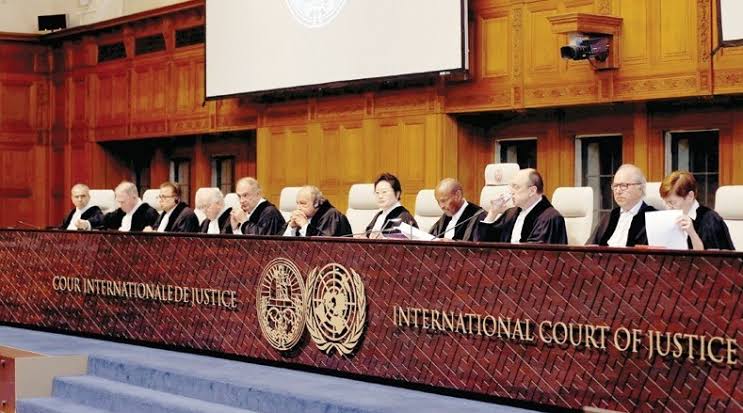

The Theory of Separation of Powers has a few key elements to it as Montesquieu envisioned; (a) The same person should not form a part of more than one of the three organs of the government. (b) One organ of the government should not interfere with any other organ of the government. (c) One organ of the government should not exercise the functions assigned to any other organ. From a prima facie inspection in regards to these principles, it is clear that in India, there is a functional overlapping in the three organs which deviates from Montesquieu’s third principle. The Doctrine of Judicial review allows the courts to invalidate certain laws passed by the legislature if they are unconstitutional while the executive can also be said to have certain impact on the structure of the judiciary as it reserves the power to make appointments to the offices of the chief justice and other judges. “Even in the United States of America where the Doctrine Of Separation of powers finds itself most vigorously canvassed, it has not found favour in absolute undiluted form”(Bakshi 1956, 553). The intermingling of certain functions thus becomes inevitable. Durga Das Basu is of the view that “in modern practice, the theory of separation of powers means an organic separation and the distinction must be drawn between 'essential' and 'incidental' powers and that one organ of government cannot usurp or encroach upon the essential functions belonging to another organ, but may exercise some incidental function thereof” (Basu 2003, 24). This view can be read in light of the second principle that was put forward in Montesquieu’s theory and it goes further to prove that the interpretation of his theory has not been followed to the letter and its actual implementation diverges from the initial principle. This points towards the inference that a straight jacket division of powers in the strict sense of the Doctrine of Separation of Powers is undesirable in a democracy.

The water-tight separation of the functions of the three organs of the government is not only unfeasible but also impractical as the inherent nature of their functions requires a certain degree of interdependency. A situation where there is an absolute division between their powers or functions would lead to less effective governance. Taking example of the judiciary, its legislative functions include inter alia, making rules for its own practice and procedure and filling gaps in law where the law remains silent on an issue which the courts are faced with. The executive powers of the judiciary include the power to appoint officers and servants of the high court. Although there are some intended overlaps between the functions or powers between the organs, there still remains an essential and organic division between their powers as is clear from Bankey Singh v Jhingan Singh, A.I.R [1952] Patna 166, where the court held that “"The State Legislature is not competent to reverse the decisions and orders of the court because the power to nullify the decrees and orders of the court is purely a judicial power and the Constitution does not appear to have given jurisdiction to the legislature either expressly or by necessary intendment to arrogate to itself the power to adjudicate a power which is exclusively within the jurisdiction of the court.” The court in this case, took it upon itself to outline that the state legislature overreached and encroached upon the powers of the judiciary in accordance with Montesquieu’s second principle and this reaffirms that there exists a division of power between the organs although it may not be water-tight.

The Doctrine of Separation of Powers, insofar as its implementation in India is concerned, has neither been given official status in the constitution nor in any statute but has been recognised and been given effect through decisions of the courts in specific regard to the Basic Structure Doctrine. It can be argued that the Doctrine of Separation of Powers has been used as a “guiding philosophy”(Garg 1964, 331-338) in governance in India. The Indian democratic system lays out a framework which presupposes separation of powers, gives it effect and re-interprets it according to the requirements of effective governance. A complete and water-tight separation, not only being an impossibility but of detrimental impact to the organs, can not be adopted in any democratic state as has been realised in India. If there is one thing that remains constant throughout the independent interpretations of the Doctrine of Separation of Powers in the democracies throughout the world, it is that the independence of judiciary is of paramount importance to maintain balance among the three organs of the government. It can therefore be supported that “there can be no liberty if the judicial powers be not separated from the legislative and the executive” (Garg 1964, 331-338). There would be an end of everything if the same body was entrusted with the powers of the three separate organs and the life and liberty of the people would become subject to arbitrary control, and the vitality of the Doctrine of Separation of powers can be understood through the realisation of the consequences of it not being there in the first place. Although, in theory a plain division of powers between the three organs of the government as Baron de Montesquieu envisaged seems viable, In India and throughout the democratic sphere, the doctrine can not be implemented in its strict sense.

REFERENCES

- Bakshi, P. M. 1956 "Comparative Law: Separation of Powers in

India." American Bar Association Journal 42, no. 6 : 553-95. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/25719656 - Basu, DD 1986 Administrative Law Kamal Law House, Kolkata.

- Marsh, Norman S. 1959 “Report of the committee on the Judiciary and the Legal Profession under the Rule of Law” The Rule of Law in a Free Society. https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/1959/01/Rule-of-law-in-a- free-society-conference-report-1959-eng.pdf

- Bakshi, P. M.1956 "Comparative Law: Separation of Powers in India." American Bar Association Journal 42, no. 6 : 553-95. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/25719656

- Garg, B. L.1964 "Problem of the Separation of Judiciary in India." The Indian Journal of Political Science 25, no. 3/4: 331-38. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/41854047