Latest Articles

Evolution of the Nature and Scope of Article 12 of the Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India is said to be the sovereign law of the land and it carries the basic nation of rule of law i.e. limited government, and provides structure, procedures, powers and duties of government institutions, and goes on to set fundamental rights, directive principles of state policy and the duties of a citizen. The whole constitutional scheme prohibits all of the three organs – the legislature, executive and judiciary from acting against the spirit of the Constitution of India. Further, the Constitution prohibits the State from interfering with the individuals’ fundamental rights. The State does not have the power to act arbitrarily, irrationally or unfairly against any said individual and can not impose unreasonable restrictions on a citizen’s fundamental rights.

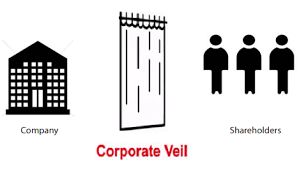

However, all such constitutional remedies are available against State’s action only. In other words, these fundamental rights can solely be enforced against the State only and not against another private individual. The limited enforcement of fundamental rights involves serious implications, and asks what would happen if private entities or non-state actors performing public duties violate individuals’ fundamental rights.

Article 12 of the Indian Constitution defines state to include the Government and Parliament of India, the Legislatures and state Governments, all local authorities and other authorities within the territory of India or under the control of the Indian Government. The most problematic expression under this article is “other authorities”, as it has not been defined. Thus, it leaves this term at the interpretation of courts and hence it is clear that the wider this term is interpreted, the wider the ambit of fundamental rights would be.

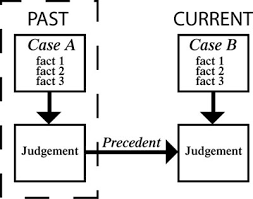

In the case of University of Madras v. Shanta Bai, the Court evolved the principle of ‘ejusdem generis’ which meant only the authorities that perform governmental or sovereign functions can be included under Article 12. The Court in this case used strict interpretation on the term ‘State’, treating it exhaustively. In the case of Rajasthan Electricity Board v. Mohan Lal, the Court held that ‘other authorities’ included those authorities which had been created by the Constitution or any other statute whose power was conferred upon by law and the fact that some of the powers were for the purpose of carrying out commercial activities was immaterial to deciding this. J. Mathew, in the case of Sukdev Singh v. Bhagatram, Court went further and held that a state acts through the instrumentality or agency of natural or juridical persons. The questions to be addressed is ‘Whether the State has financial and administrative control over the management and policies of the agency?’, ‘Whether the entity is performing an essential public function?’ and ‘Whether the entity is carrying out business for the benefit of the public or not?’. The case of Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib laid down an inclusive definition of the state having deep and persuasive control over the entity. In M C Mehta v. Sri Ram Fertilizers Ltd., 1987 SCR 819 with regard to private entities, the meaning of State action was widened. In J P Unnikrishnan v. State of A.P., it was held that private educational institutes can not be allowed to violate Article 14 as they perform a public function and this interpretation is required in the impartation of free and compulsory education. The case of Zee Telefilms Ltd., v. Union of India held that the Government had only regulatory control over the Board and hence is exhaustive. There have been a number of other cases where the Court has interpreted strictly and liberally, making the definition exhaustive and inclusive in nature based on the surrounding circumstances.